The Juggling Women at Beni Hasan:

a survey of modern practitioners

People have been juggling for thousands of years. We have the same bodies, the same gravity, the same objects to throw, and the same desire to explore the world around us.

This study asks: Can we identify the juggling patterns depicted in ancient funerary chapels? Are today’s jugglers still performing the same tricks?

Intro/History

The tombs at Beni Hasan are considered one of the best examples of middle-Kingdom art and have been studied extensively by Egyptologists for the past 200 years. However, most of the studies of the 15th and 17th tombs (where the juggling women are located) have been focused on the North wall, which depicts wrestling scenes. The jugglers have been written about in a number of journals and other publications, none of these studies have asked juggling practitioners how they interpret the paintings.

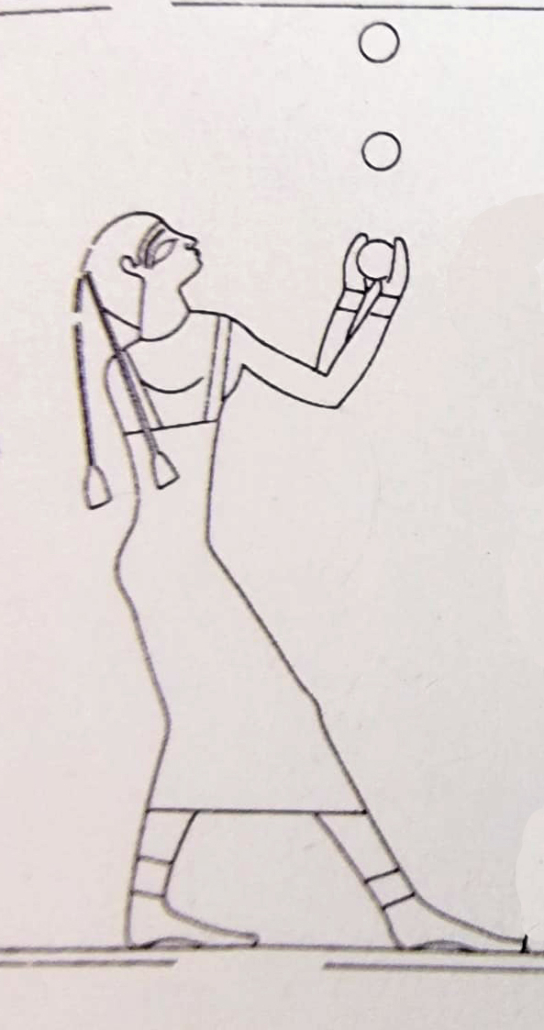

Ancient Egyptian artists were masterful, both in technique and accuracy of depiction. Different species of flora and fauna can be easily identified in their paintings–this accuracy holds significant value to modern Egyptologists as well as to botanists, ecologists, and others. Could the drawings of the Egyptian jugglers be similarly accurate?

This study is the first attempt at surveying modern jugglers (n=96) to generate data that examines the illustrations in a new way.

Methodology

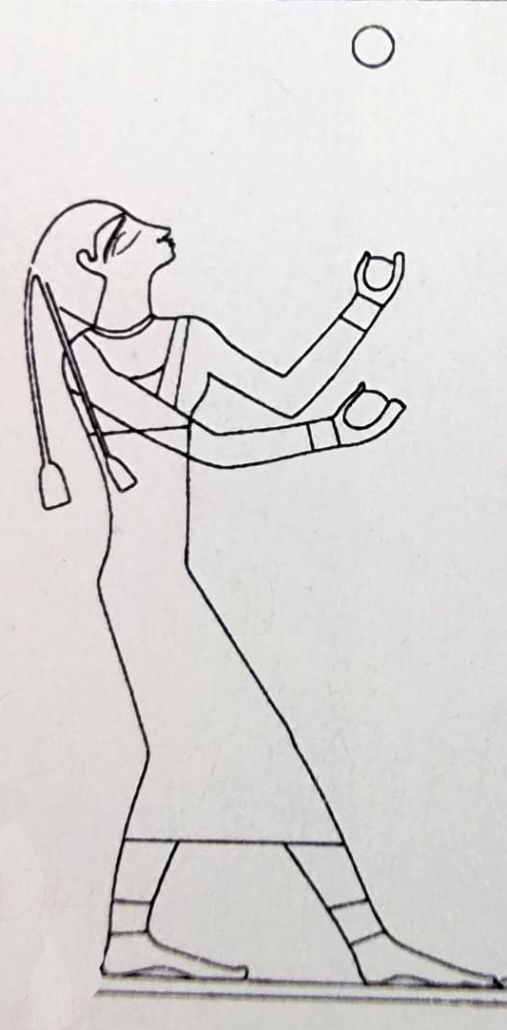

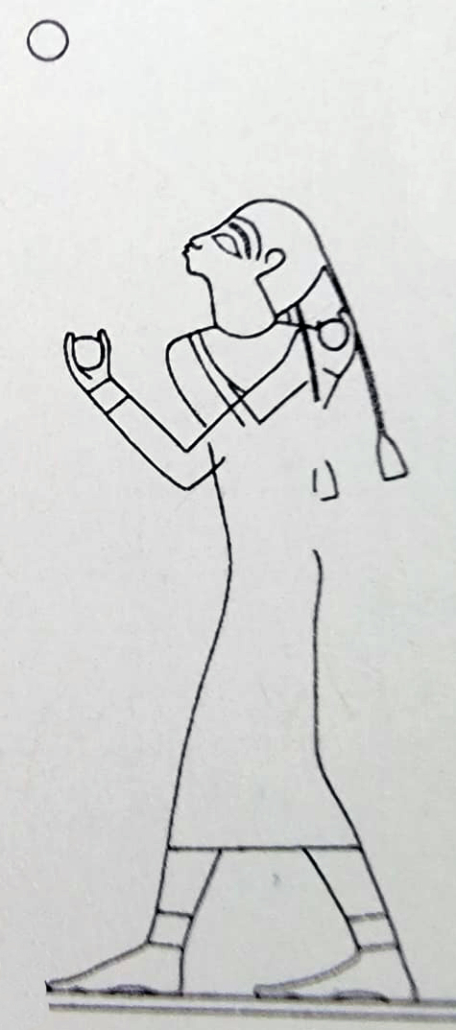

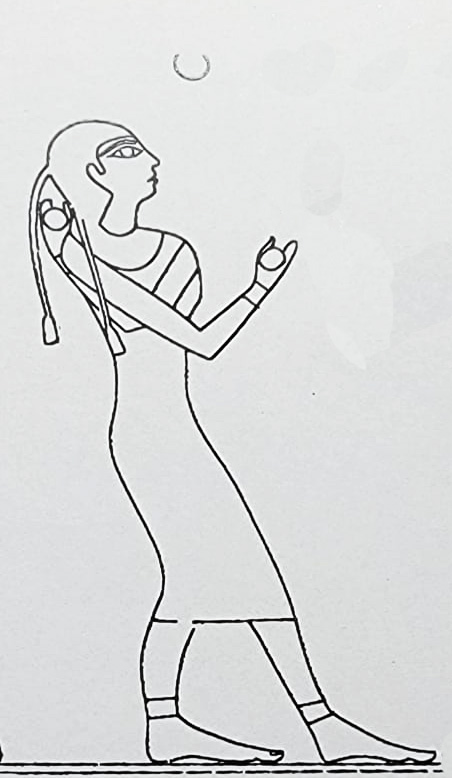

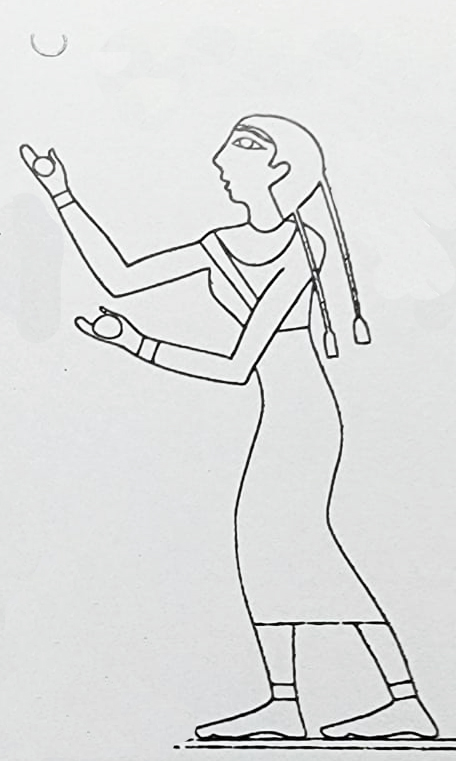

The juggling women, as drawn in Kanawati’s 2011 survey, were presented individually. Each drawing was given a unique name, starting with “15” or “17” depending on the tomb it is found in, followed by “A” “B” or “C”, indicating where they are in order, looking at the line of jugglers from left to right.

The first version of the survey was sent to a cohort of 20 expert jugglers. The survey was open-ended, looking for any possible suggestions for the patterns. Among these answers, 12 juggling patterns were independently identified by the majority of judges. These responses informed our final survey document, which included a drop-down list of these “major” answers, along with an open-ended answer if the respondent did not see their interpretation listed. This was done to help the final analysis, as many juggling patterns have multiple names or descriptors–for example, the pattern three ball box can also be described as (2x,4)(4,2x)* in modern “siteswap” notation. (Siteswap notation is a numbering system created in the 1980s that is similar to music notation. Siteswap notation assigns numerical values to objects that indicate the length of time, measured in beats, it takes for an object to return to a hand.)

It should be noted that the patterns identified by the initial 20 jugglers, which populated the final drop-down list, are considered relatively basic three-ball patterns that almost any juggler today would learn in their first year of practice.

The final survey was distributed via the International Jugglers’ Association’s electronic newsletter, eJuggle, as well as a variety of social media channels (Facebook and Instagram.) The survey was predominantly answered by jugglers of a skill level of 5+ balls and beyond (75%+ of responses.) It received 96 responses, including the first responses from the initial cohort of 20 jugglers.

The majority of responses were selected from the drop-down list. A handful of respondents used the free-form option, adding a wider variety of answers. Some of these free-form responses were alternative names for patterns on the list, and were grouped as necessary for analysis. Respondents were also allowed to respond “NA” if they did not feel confident enough to identify a pattern.

We asked about skill level as a point of demographic interest. When comparing the respondents’ self-reported technical ability with their survey answers, there was no discernable trend. That is to say, less-skilled and more-skilled jugglers tended to identify patterns in largely the same ways.

To be presented at the Mystify Magic Festival in Las Vegas, March 2025.

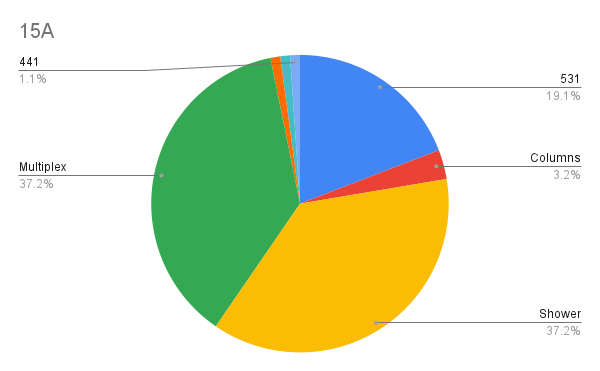

15A: 37.2% of respondents see this pattern as a shower (ss: 51). An equal percentage interpret it as a multiplex, where multiple balls are thrown from one hand at the same time. Others interpreted it as 531 (19.1%) or 441 (1.1%). Interestingly, the shower, 531, and 441 all feature the throw “1,” where an object is passed directly from one hand to the other. This means that 57.4% of respondents believe this image depicts a ball being handed from one side to the other. 1.1% of jugglers elected not to guess the pattern.

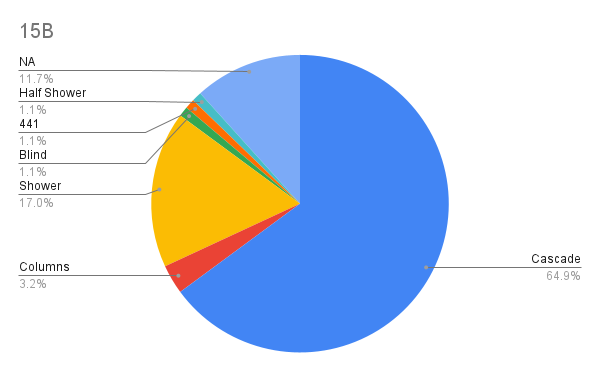

15B: The majority of respondents (64.9%) see this as the three-ball cascade, the first juggling pattern most people learn (ss: 3). 1.1% identify the drawing as the half-shower, and another 1.1% see it as the cascade performed without looking – both of which are described as “3” in siteswap. This means that 67.1% of respondents see the pattern as a cascade or variation thereof. 17.0% of respondents see a shower (ss: 51). Interestingly, a snapshot of either the cascade or the shower would look virtually identical, as they both share a moment with one ball high in the air with two balls held in the hands. 11.7% of jugglers elected not to guess the pattern.

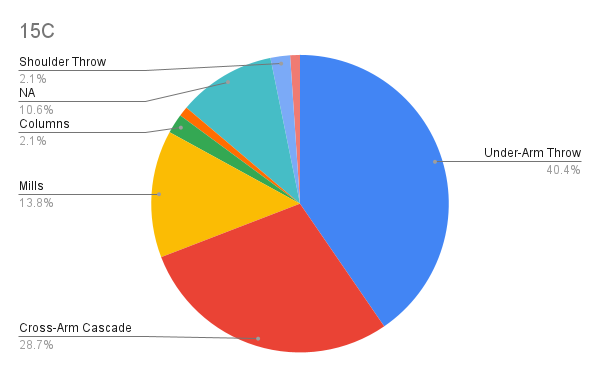

15C: 40.4% of respondents identify this image as a single under-arm throw. Other respondents interpret the drawing as a pattern that relies on multiple under-arm throws: Mill’s mess, where cross-arm throws are alternated on each side (13.8%); or a cross-arm cascade, where the arms are crossed while maintaining a three-ball cascade (28.7%). This means that 82.9% of respondents believe that this is an under-arm throw, either as a single trick or repeating pattern. 10.6% of jugglers elected not to guess the pattern.

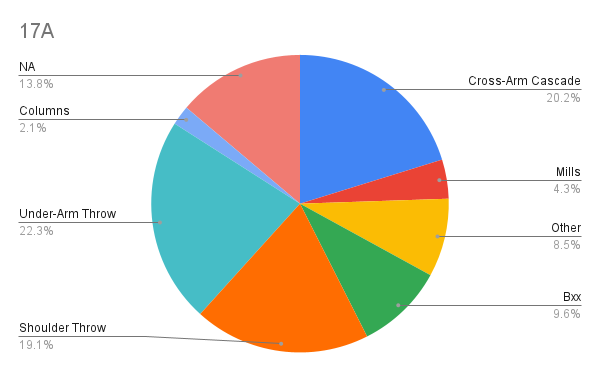

17A: As with 15C, most respondents see a pattern that relies on under-arm tosses. Unlike 15C, some respondents see some kind of “body throw” – either backcrosses (9.6%) where an object is thrown behind the back, crossing over the opposite shoulder, or a shoulder throw (19.1%) where an object is thrown behind the back, crossing over the same shoulder.13.8% of jugglers elected not to guess the pattern.

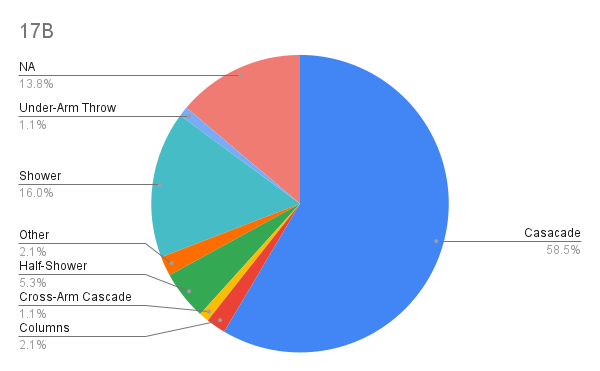

17B: 58.5% of respondents see the basic cascade pattern (ss: 3). 63.9% of respondents see either the cascade or another similar pattern that can be described as “3” in siteswap notation. (58.5% cascade, 5.3% half-shower, 1.1% under-arm throw.) A smaller percentage of respondents (16.0%) see the shower pattern (ss: 51). Interestingly, a snapshot of the cascade or the shower would look virtually identical, as both share a moment where one ball is in the air with two balls being held in the hands. 13.8% of jugglers elected not to guess the pattern.

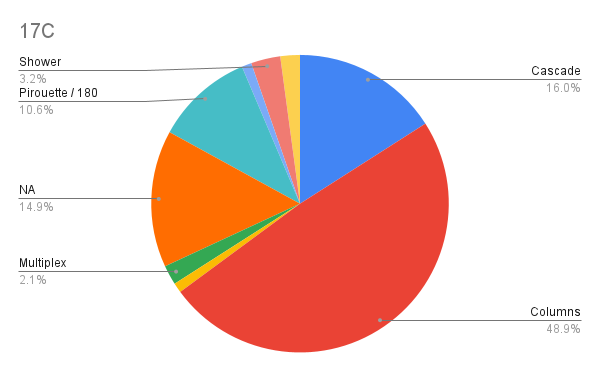

17C: 48.9% of respondents interpret this drawing as columns or “one-up, two-up” (ss: (4,0)(4,4) ). 10.5% of respondents see a pirouette or 180, where one object is thrown high and the juggler turns their body underneath the object mid-flight. 14.9% of jugglers elected not to guess the pattern.

Conclusions

The tombs of Khety and Baqt III are, in many areas, identical to one another. They depict the same scenes on the same walls, largely in the same places. It’s interesting that the drawings of the juggling women are in reverse order when comparing them (15B and 17B match, but the figures on either end swap places.)

Although these murals may be copies of one another, slight variations in hand position lead respondents to give slightly different interpretations.

15B and 17B are seen by the majority as the cascade pattern (ss: 3). However, jugglers assert this more in the case of 15B than 17B (64.9% vs 58.5% responding “cascade.”) A small but notable minority identify both of these images as “shower” or “half-shower.”

15C and 17A are surprising in their interpretations. While 82.9% of respondents say 15C depicts some kind of under-arm throw, only 46.8% say the same of 17A. Over a quarter of the jugglers surveyed (28.7%) believe 15C shows some kind of “body throw,” where the ball would be thrown behind the back or over the shoulder. Although 15C is the most faded/damaged image in the survey, 80.4% of jugglers chose to identify the pattern.

Future Study

The drawings of jugglers in the tombs of Khety and Baqt III are the only known representations of jugglers in Ancient Egypt. It is possible that another representation of jugglers could exist, yet remain undiscovered. Paintings and reliefs of acrobats and dancers in ruins up and down the Nile indicate a strong tradition in Ancient Egypt, as they depict the same postures and contortions, drawn hundreds of years thousands of kilometers apart. Could the same be true of juggling?

There are records of juggling and skill-based ball games in Ancient Greece and Rome that rely on cascade and shower patterns, starting from at least 500BCE. Most cultures around the world, no matter how isolated or remote, have some kind of juggling tradition. While it’s tempting to think that the Ancient Egyptians “exported” the practice to the rest of the globe, there is no evidence that supports this theory. Were the Egyptians the first to juggle? We will never know. The drawings they left us are the oldest record of juggling we know of, and it’s remarkable they have survived for so long, studied over 4,000 years after they were drawn.

Select Bibliography

Sport und Spiel im Alten Ägypten. Decker, W. CH Beck. Munich. 1987.

Ancient Egyptian Dances. Lexova, I. Oriental Institute. Prague. 1935.

Sport in Ancient Egypt. Touny, A.D. Wenig, S. BR Gruner. Amsterdam. 1969.

Juggling: From Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Wall, T. Modern Vaudeville Press. Philadelphia. 2019.

Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province. Kanwati, N. The American University in Cairo Press. Cairo. 2011.

Special Thanks

Special thanks to: Dr. L. Lewis Wall, Benjamin Domask-Ruh, Felice Ling, Joshua Lee, Sophie Lewis.

Learn More

Want to learn more about ancient juggling practices from around the world? Juggling: From Antiquity to the Middle Ages has you covered!

This book is the “first modern survey of juggling in the ancient world” — and is used as an anthropology textbook in universities across the US and Europe. Give it a read!

Poster Download

Want to use this poster for something? You can download the PDF here!